What is Health Economics

Health Economics is an applied field of study that allows for the systematic and rigorous examination of the problems faced in promoting health for all. By applying economic theories of consumer, producer and social choice, health economics aims to understand the behavior of individuals, health care providers, public and private organizations, and governments in decision-making.

Health economics is used to promote healthy lifestyles and positive health outcomes through the study of health care providers, hospitals and clinics, managed care and public health promotion activities. The MHS in Global Health Economics degree program in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health uses health economic principals to address global issues such as migration, displaced persons, climate change, vaccine access, injuries, obesity and pandemics.

Health economists apply the theories of production, efficiency, disparities, competition, and regulation to better inform the public and private sector on the most efficient, cost-effective and equitable course of action. Such research can include the economic evaluation of new technologies, as well as the study of appropriate prices, anti-trust policy, optimal public and private investment and strategic behavior.

Faculty in the Department of International Health are currently conducting research on a wide variety of topics, including the impact of health care, health insurance and preventative services on health lifestyles, as well as providing research and advice to governments around the globe to enable a more effective and equitable allocation of resources.

Read more about careers in health economics.

Applying economics in everyday life

At the start of the academic year, I always feel a little pressure to justify the study of economics. Students come up asking things like, should they do economics or history? It’s hard to know what to say, but to get people excited about economics it’s good to try and think how economics can be applied in everyday life. Some of this is just common sense, but economics can help put a theory behind our everyday actions.

Buying goods which give the highest satisfaction for the price

This is common sense, but in economics, we give it the term of marginal utility theory. The idea is that a rational person will be evaluating how much utility (satisfaction) goods and services give him compared to the price. To maximise your overall welfare, you will consume a quantity of goods where total utility is maximised given your budget. For example, is it worth paying extra charges by airlines, such as paying for more leg-room? Or pay to get priority boarding? Economics suggests we need to evaluate the marginal benefit of these services compared to the marginal cost. See: Extra charges by airlines

Sunk cost fallacy

A sunk cost is an irretrievable cost, something we cannot get back. For example, suppose we sign up for a gym membership at $40 a month for a whole year. We are committed to paying $480, whether we go or not. If we are feeling unwell, should we go to the gym to get our money’s worth or should we write off the sunk cost and maximise our marginal utility for that particular day? See: sunk cost fallacy

Opportunity Cost

The first lesson of economics is the issue of scarcity and limited resources. If we use our limited budget for buying one type of good (food), there is an opportunity cost – we cannot spend that money on other goods such as entertainment. Opportunity cost is an intrinsic aspect of most economic choices. We may like the idea of lower income tax, but there will be an opportunity cost – in this case, less government revenue to spend on health care and education.

There’s no such thing as free parking

Another example of opportunity cost – no one likes to pay for parking, but would we be better off if parking was free? Most likely not. If parking was free, demand might be greater than supply causing people to waste time driving around looking for a parking spot. Free parking would also encourage people to drive into city centres rather than use more environmentally friendly forms of transport. The result would be that free parking would increase congestion; therefore although we would pay less for parking, we would face other indirect costs. (time wasted)

Behavioural economics and bias

Traditional economic theory assumes that man is rational. However, the work of behavioural economics suggests we can be prone to bias and irrational behaviour. For example, we may be prone to a present bias where we overvalue pleasure in the short-term and ignore long-term implications. For example, consuming demerit goods like alcohol or not saving sufficiently for retirement. The insight of present bias suggests we make decisions our future self would not make. If we become aware of these bias and irrational behaviour, then we can make better decisions which improve our long-term welfare.

See: Behavioural economics

Irrational exuberance

Another issue in behavioural economics is that of irrational exuberance or when we get carried away by an asset bubble. Can we be sure we will not get carried away by a boom and bubble? History suggests that many investors are over-optimistic about their ability to leave the market at the optimal time and can feel that this time is different.

See: Irrational exuberance

On the other hand

In economics, there’s always another way of looking at the world. Borrowing is bad, except when it isn’t. Nothing is black and white in economics; it depends. For example, government borrowing to finance pensions for an ageing population can lead to an unsustainable rise in government debt. However, government borrowing during a recession can help the economy recover.

Diminishing returns

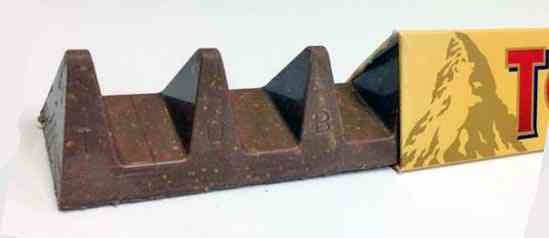

If we like chocolate cake, why do we not eat three per day? The reason is diminishing returns. The first chocolate cake may give us 10/10. The second cake 3/10. The third cake may make us sick and give a negative utility. People may have different opinions about when diminishing returns set in. Some students may feel this is after the second pint, other students only after considerably more. There are also diminishing returns to money. That is why we don’t spend all our time working – extra money gives increasingly less satisfaction and reduces leisure time

DIminishing returns to wealth/income

A similar concept is that of diminishing returns to wealth and income. Does an extra $100 give us more utility? Yes, but it depends on our current income. If we have a very low salary, the extra $100 will make a big difference. But, if we earn $100,000 a year, we may not notice that extra $100 a year. The importance of this is for choosing the right balance between work and leisure. What is the value in working a long working week, if the extra money earnt has a limited marginal utility?

Externalities

Economics may feel we are promoting selfish ends – firms maximise profits, consumers maximise their personal utility. Adam Smith claimed pursuing selfish goals ended up in improving the greater good. But, in economics, we also try to consider the impact of our actions on other people. If a firm produces chemicals, it may make a profit, but cause an external cost of pollution. To ignore this external cost would be to create an inefficient outcome. We should make the firm pay the cost of its pollution so that it has the incentive to minimise or halt external costs. Externalities are everywhere. Even your decision to study economics could have positive externalities in the future. For example, you could end up being an economics teacher helping others learn all about economics.

Public goods not provided by the free market.

The free market has many advantages. Private firms tend to be more efficient, innovative and respond to consumer preferences. However, many goods and services would either be not provided or under-provided in a free market. Public goods like street lighting and law and order. Also, public services like health care and education would be provided in insufficient quantities. Therefore, to optimise social welfare there is a need for government intervention through taxes and direct public provision. We may dislike taxes, but we would dislike not being able to see a doctor.

Should I worry about automation and new technology?

There are concerns that new technology and automation will lead to job losses and some people losing out. If our job is threatened by new technology is the fear justified? Economic analysis suggests there it is a fallacy that new technology leads to permanent job losses. This is known as the Luddite Fallacy – though some jobs are lost, new ones are created. Automation and new technology are not guaranteed to make everyone better off – especially in the short term. See: Pros and cons of automation

Macroeconomics affects everyone

Everyone is affected in some way by macroeconomic issues such as inflation and unemployment. Inflation can reduce the value of your savings. If you keep cash under your bed during high inflation, you’d be better off trying to buy gold or some physical assets. Mass unemployment can cause society to fragment, therefore there is a need to adopt policies to try and reduce unemployment.

Life-cycle hypothesis

The Life Cycle Hypothesis states that to maximise lifetime utility, we should try to smooth our consumption patterns over the course of our life. It is not good to have substantial income when we are old and unable to move. Spending some money in our student years will give greater overall utility. This justifies taking out a student loan to pay back when we are working and then saving for a pension in our retirement.

Examples of economics in everyday life

Related

Last updated: 10th November 2021, Tejvan Pettinger, Oxford, UK

Importance of economics in our daily lives

Economics affects our daily lives in both obvious and subtle ways. From an individual perspective, economics frames many choices we have to make about work, leisure, consumption and how much to save. Our lives are also influenced by macro-economic trends, such as inflation, interest rates and economic growth.

Summary – why economics is important

The opportunity costs we face in deciding what to buy – how to use time

How to maximise our economic utility and avoid behavioural bias

How the macro-economic – inflation, economic growth and employment prospects affect our living standards.

Individual markets like housing market can influence our standard of living.

Understanding issues like externalities. We may not like paying petrol tax, but if we see it helps to reduce pollution and congestion and the tax revenue is used to subsides public transport, it gives a different perspective.

Economic choices – opportunity cost

We are constantly faced with choices. It may be a matter of limited time. For example, at the weekend:

We could spend 8 hours working in a cafe at the Minimum Wage of £7.83

Or we could spend 8 hours studying for our A-Levels.

Alternatively, we could choose to spend 8 hours of leisure (sleeping in, Facebook

Each choice has an opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of earning 8*£7.83 = £62.64 is that we don’t have time to study. This could lead to poorer exam results, which could lead to lower future earning potential. Choosing to maximise our income in the short term (earning £62 a day) may reduce our lifetime earnings and could be a poor decision – unless working in a cafe doesn’t affect our future earnings. We may feel job experience more useful than an essay on allocative efficiency.

The problem is that when making decisions about whether to study, work or pursue leisure, we may forget or ignore long-term effects. Deciding to spend all our free time earning £62 is something we may regret later in life. Economists suggest education is a merit good – meaning people may underestimate the benefits of studying. Under-consumption of education is an example of market failure.

Considering opportunity cost can help us make better decisions. If we act on instinct, we may choose the most pleasurable or easiest course of action, but the best decision in the short term may not be best in long term.

Choice of study vs leisure

A production possibility frontier showing a simple trade off – time spent working or time spent on leisure.

Work

Another important element of life is work. Which job will give the most satisfaction? It is not just about finding a well-paid job, we tend to gain most job satisfaction when we feel part of the process and a degree of responsibility and influence. Behavioural economists such as Dan Ariely have examined motivations for work and find that income/bonuses is less important than suggested by neo-liberal economic theory.

Nudges and rational behaviour

In traditional economics, it is assumed individuals are rational and utility maximising. In other words, it is assumed we calculate decision to maximise our economic welfare – spending money only on those goods which give us satisfaction.

However, behavioural economists note that we are often influenced by irrational and non-utility maximising influences. For example, companies which ‘nudge‘ us to make decisions which harm our welfare – e.g. super-sized portions, we don’t really need but cause us to become less healthy.

The importance of the insights of behavioural economics is that we can become aware of factors which may cause us to make sub-optimal decisions. We can try to resist commercial nudges – which encourage us to consume goods which don’t really benefit us.

Behavioural economics and bias

A recent development in economics is the work of behavioural economics – which places more emphasis on elements of psychology. For example, are humans really rational utility maximisers – as suggested by traditional economic theory? Behavioural economics suggests not – but humans are influenced by emotional factors, such as loss aversion (we prefer the status quo, to losing what we have), present time period bias.

Importance of the macroeconomy on our daily lives

When making decisions we don’t tend to first look at leading economic indicators. But, perceptions about the economic outlook can influence certain decisions. For example, those aware of the current economic situation may be aware the depth of the recession which makes a period of low-interest rates more likely. This suggests that if you could get a mortgage, mortgage payments would be cheaper, but, saving would give a poor return.

However, the bad state of the economy and high unemployment rate is a factor that may encourage students to stay on and study. Since youth unemployment is currently very high, it makes more sense to spend three years getting a degree rather than going straight on to the job market.

The only problem is that many other students are thinking the same. Hence the competition for university places is becoming much stronger.

How to survive a period of inflation?

Suppose, we are living in a period of high inflation, how would that affect our economic welfare?

The real value of our savings will decline – unless we can secure an interest rate higher than the rate of inflation. In periods of high inflation, it may be advisable to take out index-linked savings – saving accounts and bonds which give an interest rate related to the inflation rate.

If we cannot secure a good interest rate, an option is to invest in commodities or assets which can protect their value better than ordinary savings accounts

How will we be affected by rising interest rates?

If interest rates increase, then it will increase the cost of mortgage payments and interest on loans and credit cards. It can be problematic for individuals who are over-extended on credit. Higher interest rates can also lead to a slowing economy and increase the risk of unemployment.

Mortgage affordability. High-interest rates in the late 1980s caused mortgage payments to take over 50% of take-home pay from households.

See The effect of higher interest rates.

Investing

If we are considering investing in the stock market or housing market, what can economics teach us?

One cautionary tale is that of irrational exuberance – avoid getting caught up in asset booms – where investor confidence gets carried away and people end up buying shares/assets – even though the price has become overvalued.

Externalities

When choosing what to consume and produce, we often ignore externalities. For example, driving into city centre may contribute to pollution and congestion. The social cost of driving is higher than the private cost. Would our living standards be increased by supporting a congestion charge? At first glance, no – we pay higher taxes. But, if there are external costs a higher tax can lead to a more socially efficient level.

A tax can shift output from Q1 to Q2 (which is more socially efficient)

Limitations of economics

As a final thought – is economics overvalued? As a society do we give too much weighting to maximising income, profit and GDP? In a sense, traditional economics encourages us to view life from an economic/monetary perspective. But, perhaps this causes us to miss out on more important issues, such as spiritual understanding, concern for the environment, concern for others and getting the correct work/life balance.

Related