China’s economy is in bad shape and could stay that way for a while

Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

Hong Kong CNN Business —

China is beset by severe economic problems. Growth has stalled, youth unemployment is at a record high, the housing market is collapsing, and companies are struggling with recurring supply chain headaches.

The world’s second biggest economy is grappling with the impact of severe drought and its vast real estate sector is suffering the consequences of running up too much debt. But the situation is being made much worse by Bejing’s adherence to a rigid zero-Covid policy, and there’s no sign that’s going to change this year.

Within the past two weeks, eight megacities have gone into full or partial lockdowns. Together these vital centers of manufacturing and transport are home to 127 million people.

Nationwide, at least 74 cities had been closed off since late August, affecting more than 313 million residents, according to CNN calculations based on government statistics. Goldman Sachs last week estimated that cities impacted by lockdowns account for 35% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The latest restrictions demonstrate China’s uncompromising attitude to stamping out the virus with the strictest control measures, despite the damage.

“Beijing appears willing to absorb the economic and social costs that stem from its zero-Covid policy because the alternative — widespread infections along with corresponding hospitalizations and deaths — represents an even greater threat to the government’s legitimacy,” said Craig Singleton, senior China fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a DC-based think tank.

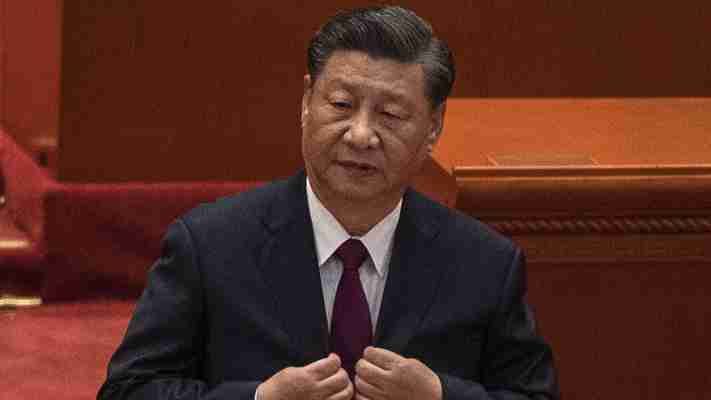

For Chinese leader Xi Jinping, maintaining that legitimacy is more vital than ever as he seeks to be selected for an unprecedented third term when the Communist Party meets for its most important congress in a decade next month.

“Major policy shifts before the party congress appear unlikely, although we could see a softening in certain policies in early 2023 after Xi Jinping’s political future has been assured,” Singleton said.

“Even then, the Party is running short on both time and available policy levers to address many of the most pressing systemic threats to China’s economy,” he added.

The economy will continue to worsen in the next few months, said Raymond Yeung, chief Greater China economist for ANZ Research. Local governments will be “more inclined to prioritizing zero-Covid and snuffing out the virus outbreaks” as the party congress approaches, he added.

Tightening of Covid restrictions will hit consumption and investment during China’s “Golden September, Silver October,” traditionally the peak season for home sales.

In the meantime, a sharp slowdown in the global economy doesn’t bode well for China’s growth either, Yeung said, as weakening demand from the US and European markets will weigh on China’s exports.

He now expects Chinese GDP to grow by just 3% this year, missing Beijing’s official target of 5.5% by a wide margin. Other analysts are even more bearish. Nomura cut its forecast to 2.7% this week.

No exit until early 2023?

More than two years into the pandemic, Beijing is sticking to its extreme approach to the virus with forced quarantines, mass mandatory testing, and snap lockdowns.

The policy was deemed successful in the early stage of the pandemic. China managed to keep the virus at bay in 2020 and 2021 and stave off the large number of deaths many other countries suffered, while building a quick recovery following a record contraction in GDP. At a ceremony in 2020, Xi proclaimed that China’s success in containing the virus was proof of the Communist Party’s “superiority” over Western democracy.

But the premature declaration of victory has come back to haunt him, as the highly transmissible Omicron variant makes the zero-Covid policy less effective.

However, giving up on zero-Covid doesn’t seem like an option for Xi, who this year has repeatedly put greater emphasis on defeating the virus than rescuing the economy.

In a trip to Wuhan in June, he said China must maintain its zero-Covid policy “even though it might hurt the economy.” At a leadership meeting in July, he reaffirmed that approach and urged officials to look at the relationship between virus prevention and economic growth “from a political point of view.”

“Beijing has sought to cast its zero-Covid policies as evidence of the Party’s strength, and therefore, by extension, Xi Jinping’s leadership,” Singleton said.

Any change in approach may not come until next year, and even then it’s most likely to be very gradual, said Zhiwei Zhang, president and chief economist for Pinpoint Asset Management.

“It will be a long process,” he said, adding that Hong Kong — where quarantine and testing rules for visitors have recently been relaxed — could be “an important leading indicator for what will happen in the mainland.”

Another dismal quarter

While Beijing seems unwavering on its zero-Covid strategy, the government has rolled out a flurry of stimulus measures to boost the flagging economy, including a one trillion yuan ($146 billion) package unveiled last month to improve infrastructure and ease power shortages.

The government is trying to achieve “the best possible outcome” for economic growth and jobs while sticking to zero-Covid, but it’s “very hard to balance the twin goals,” said Yeung from ANZ.

Recent data suggest the Chinese economy could be headed for another dismal performance in the third quarter. GDP expanded by only 0.4% in the second quarter from a year earlier, slowing sharply from growth of 4.8% in the first quarter.

Official and private sector surveys released last week showed China’s manufacturing industry contracting in August for the first time in three months, while growth in services slowed.

“The picture is not pretty, as China continues to battle the broadest wave of Covid infections thus far,” Nomura analysts said in a research report on Tuesday.

Jobs and property issues

China’s job market has deteriorated in the past few months. Most recent data showed that the unemployment rate among 16 to 24 year-olds hit an all-time high of 19.9% in July, the fourth consecutive month it had broken records.

That means China now has about 21 million jobless youth in cities and towns. Rural unemployment isn’t included in official figures.

“The most worrying issue is jobs,” said ANZ’s Yeung, adding that youth unemployment could climb to 20% or higher.

Other economists say more job losses are likely this year as social distancing measures hurt the catering and retail industries, which in turn piles pressure on manufacturers.

The deepening property market downturn is another major drag. The sector, which accounts for as much as 30% of China’s GDP, has been crippled by a government campaign since 2020 to rein in reckless borrowing and curb speculative trading. Property prices have been falling, as have sales of new homes.

While there could be a relaxation of zero-Covid rules in 2023, housing policy may not look very different after the party congress.

“We are unlikely to see the economy repeat the previous high growth of 5.5% or 6% for the next two years,” said Yeung.

World Economic Situation and Prospects: September 2022 Briefing, No. 164

A bleak outlook for the global economy: Slowing growth, high and persistent inflation, and elevated uncertainties cloud global economic outlook

The global outlook has deteriorated markedly throughout 2022 amid high inflation, aggressive monetary tightening, and uncertainties from both the war in Ukraine and the lingering pandemic. Soaring food and energy prices are eroding real incomes, triggering a global cost-of-living crisis, particularly for the most vulnerable groups. Growth in the world’s three largest economies—the United States, China, and the European Union—is weakening, with significant spillovers to other countries. At the same time, rising government borrowing costs and large capital outflows are exacerbating fiscal and balance of payments pressures in many developing countries. Against this backdrop, the global economy is now projected to grow between 2.5 and 2.8 per cent in 2022, a substantial downward revision from our previous forecasts released in January and May 2022. While the baseline forecast for 2023 is highly uncertain, most forward-looking indicators suggest a further slowdown in global growth.

The manufacturing purchasing managers’ indexes—one key measure of business confidence—experienced broad-based declines during the past six months (figure 1). The deterioration in business confidence is particularly alarming for many developing countries that are yet to fully recover from the pandemic. International food and energy prices have fallen from recent peaks but continue to be at very high levels (figure 2). Global trade remains largely subdued as global supply chain disruptions and bottlenecks in international freight movements persist. The upward price pressures—reaching multi-decade highs in many countries—are hitting vulnerable population groups hard and prompting central banks to quickly tame inflation.

The world’s largest economies are facing sharp growth slowdowns

The economic outlook for the United States has deteriorated considerably amid high inflation, tight labor market conditions and aggressive monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve. After expanding by 5.7 per cent in 2021, GDP contracted in both the first and second quarters of 2022. Full-year growth forecasts have been downgraded to only about 1.5 per cent in 2022. Consumer spending, which accounts for about 70 per cent of economic activity, is expected to soften despite a still buoyant labor market that has recovered all the 22 million jobs lost at the outset of the pandemic. Amid an increasingly tight labor market, average hourly earnings in the private sector rose by 5.4 per cent in the first half of 2022. But with inflation averaging about 8.3 per cent during the same period, households are seeing their purchasing power erode and may start cutting back spending. Meanwhile, the strong dollar—which remains close to a 20-year high—will continue to exacerbate the US trade deficit. The housing market has taken a hit due to higher mortgage rates and soaring building costs, with residential fixed investment and home sales declining.

Growth in China is projected to slow to about 4 per cent in 2022 due to new waves of COVID-19 infections and rising geopolitical risks. In the second quarter, GDP growth fell to a two-year low of 0.4 per cent as strict measures were introduced to control the rise in cases of the Omicron variant of COVID-19. The growth momentum is expected to strengthen in the second half of 2022 and into 2023. Accelerated issuance of local government special bonds is set to boost infrastructure investment, while tax cuts will support businesses. With inflation below target, the central bank has maintained its supportive policy stance and lowered both its 5-year and 1-year rates in recent weeks. The Chinese economy faces major downside risks, including the re-emergence of new and highly transmittable variants of COVID-19. Although deleveraging measures in the real estate markets could improve macroeconomic stability in the medium term, they could trigger a wider financial sector crisis in the near term. In addition, still elevated urban unemployment could weigh on the recovery of private consumption. Rising geopolitical tensions between China and the United States add further uncertainties to the outlook.

The economies in Europe have so far proved resilient to the fallout from the war in Ukraine, but strong headwinds and downside risks persist. The region is facing triple pressures from the energy crisis, high inflation, and monetary policy tightening. Following a robust expansion in the first half of 2022—driven by further relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions and pent-up demand for services—GDP in the European Union is projected to grow by about 2.5 per cent this year. A potential total shut-down of Russian gas during the upcoming winter could lead to severe energy shortages and likely push Germany, Hungary, and Italy into recessions. Soaring energy and food prices are hurting households, with consumer confidence hitting a record low in July, falling even below the level at the beginning of the pandemic. A strong rebound in the labor market and exceptionally low unemployment rates in the European Union—ranging from 2.4 per cent in Czechia to 12.6 per cent in Spain—will likely provide some support to domestic demand.

Economies in transition show resilience

The economic prospects for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Georgia are heavily affected by the conflict in Ukraine and the stringent sanctions against the Russian Federation. Economic activity in the Russian Federation has so far defied expectations, with GDP declining by only 4 per cent in the second quarter of 2022. The strong appreciation of the Russian ruble helped stabilize inflation, sustaining private consumption and allowing the central bank to drastically cut policy rates. GDP is now forecast to contract by about 6 per cent in 2022, relative to our earlier projection of a 10.6 per cent decline. Most other CIS economies have also shown strong resilience, with the region’s energy exporters benefiting from high oil and gas prices. Inflation, however, reached very high levels across the region in recent months, threatening food security and forcing many central banks to sharply tighten their policy stances. The Ukrainian economy, however, faces enormous challenges, including destruction of physical infrastructure, suspension of production and trade activities, and displaced population. The post-conflict reconstruction will require immense financial resources.

Prospects for developing countries are weakening amid multiple challenges…

Many developing countries are fighting an uphill battle to fully recover from the pandemic, with high inflation, rising borrowing costs and the slowdown in the major economies further hurting their growth prospects. Despite the windfall of high commodity prices for the commodity-exporters in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, growth remains largely insufficient to mitigate the slack in labor markets. The ILO estimates that in developing countries, the gap in hours worked relative to pre-pandemic levels stood at— 6.0 per cent in the second quarter of 2022, compared to only—1.5 per cent in high-income economies.

In Africa, the slowing external demand from the European Union – its main trading partner, representing about 33 per cent of African exports – and waning monetary and fiscal support are constraining the recovery. Surging energy prices are benefiting oil-exporting countries, but net energy importers face rising pressures on current and fiscal accounts. Amid elevated levels of debt and rising borrowing costs, several governments are seeking bilateral and multilateral support to finance public investments. In many countries, there is increasing pressure to cut spending or raise taxes. Risks to regional security and domestic stability are rising as frustration mounts over inflation, lack of employment, and economic mismanagement.

The outlook in Latin America and the Caribbean remains challenging, amid aggressive monetary tightening, slowing growth in China and the United States, and domestic political uncertainties in some countries. Inflation remains close to multi-year highs in many countries. Higher oil prices are providing a windfall to oil-exporters such as Colombia, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Ecuador. Growth in Brazil – the largest economy in the region – remains subdued as fiscal cuts and political uncertainty add to the challenges. Given the region’s weak growth prospects, the scars from the pandemic will last for years, with poverty projected to increase further in 2022.

East Asia’s growth is expected to weaken in 2022. Higher commodity prices and rising interest rates are set to curtail spending and investment and slow the recovery. In addition, external demand is expected to soften as growth in the region’s main trading partners slows. In South Asia, higher global energy and food prices are severely affecting food insecurity. Tightening financial conditions, depreciation of domestic currencies and the spillover effects from the Ukraine conflict are creating fiscal and balance of payments pressures. India’s GDP growth is moderating, as high inflation and rising borrowing costs weaken domestic demand. Sri Lanka’s severe debt crisis, which has been accompanied by a major energy emergency and shortages of food and other essentials, illustrates the potential risks for many developing countries – most notably energy and food importers. In Western Asia, economic growth prospects have slightly improved due to high energy prices and waning adverse effects from the pandemic.

The outlook in the least developed countries (LDCs) – whose economies are most vulnerable to external shocks – is extremely challenging. As most LDCs are food and oil importers, the rise in global prices and the disruptions of global food supplies are severely impacting these economies, raising fiscal and balance of payment financing needs and increasing food insecurity. Growth is projected to remain weak in 2022, as rising food and energy prices increase living costs, erode real incomes and weaken domestic demand. Risks of a lost decade for many LDCs are rising amid high debt vulnerabilities and severe structural constraints, including insufficient fiscal space, large macroeconomic imbalances and lack of productive capacities. The short-term outlook in small island developing States (SIDS) also remains bleak, as tourism has not fully recovered from the pandemic. In 2022 the global tourism sector may reach 55 to 70 per cent of pre-pandemic levels, according to the UNWTO. In Asia and the Pacific, tourist arrivals in the first five months of 2022 were still almost 90 per cent below the 2019 level.

A global food crisis is hitting many developing countries

The war in Ukraine is severely affecting global food supplies. Food prices remain close to record highs, surpassing levels seen during the global food crises of 2007-2008 and 2010-2012, which sparked worldwide protests, particularly in Africa. A recent agreement between Ukraine and the Russian Federation to allow the resumption of grain exports from Ukrainian ports provided some relief, but its duration remains uncertain, and the conflict still weighs on Ukrainian agricultural production. The war is also contributing to high energy prices, which will affect forthcoming harvests as farmers cut back on sowing and planting given the high cost of running farm equipment, transportation, and fertilizer. A scorching summer season and increasing climate-related disasters are adding uncertainty and putting harvests at risk. Food prices are projected to stay high, and the risk of severe food shortages could remain for years.

Amid high food and fertilizer prices, the appreciation of the dollar and diminished fiscal space, low-income countries in Asia and Africa are most at risk. For example, food insecurity has exacerbated in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Sudan. A few developing countries are implementing or considering food export restrictions (e.g., India, Indonesia, Malaysia), which in turn will raise the cost of food imports for others. In addition, many governments are struggling to subsidize vulnerable households most at risk, as well as supporting farmers. A scramble for food may push millions into famine and cause social unrest and mass migration. High prices have already provoked protests in countries such as Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Sudan.

The global food crisis presents a major challenge to sustainable development. In June 2022, the UN warned that the world is moving further away from its goal of ending hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms by 2030. The number of people, particularly women, facing severe food insecurity has soared from 135 million in 53 countries before the pandemic to 345 million in 82 countries.

Central banks are changing course: Surging inflation prompts aggressive monetary tightening

After a long period of price stability, inflation has returned with a vengeance in many countries (figure 3), eroding real incomes and triggering a global cost-of-living crisis. The pandemic-induced inflationary pressures have proved to be persistent, with demand recovering quickly and supply facing major hurdles and disruptions. The war in Ukraine, soaring food and energy prices and renewed supply shocks have not only fueled a surge in inflation, but also pushed up short – and medium-term inflation expectations. In the United States, core inflation rose by 5.9 per cent year-on-year in July, while in the euro area the index increased by 4 per cent, the highest rate since the common currency was introduced.

Inflation in many large developing economies has also accelerated and is now generally well above the comfort zone of the central banks. In Mexico, for example, annual inflation increased to 8.2 per cent in July 2022, the highest rate in more than 20 years. Similar upward trends are observed in Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, Indonesia, and South Africa. The impact of rising living costs is much higher in the least developed countries with a large share of their population already living in poverty. The food crisis will likely increase the number of people living in extreme poverty.

Many central banks have been raising interest rates in quick succession in recent months, often opting for larger-than-usual rate hikes of 50 basis points or more to bring inflation under control and anchor inflation expectations. This shift towards tighter monetary policy is exceptionally broad-based (figure 4). About three out of four central banks worldwide have increased interest rates in 2022, reflecting the global nature of the current inflationary environment. The main exceptions to this trend are the People’s Bank of China, which reduced its key interest rates in January and August 2022 to support the economy, and the Bank of Japan, which has maintained its ultra-accommodative monetary stance, with negative short-term interest rates. Despite the recent hikes, however, real interest rates remain deep in negative territory.

Central banks in many developed countries are aiming at a “soft landing” for their economies, expecting to tame inflation without triggering a recession. The US Federal Reserve has taken a more aggressive stance than other major central banks, raising its key policy rate from 0–0.25 per cent in March to 2.25-2.5 per cent in August. By the end of 2022, the rate is projected to reach about 3.5 per cent, the highest level since 2008. The European Central Bank (ECB) raised its benchmark interest rates in July for the first time in more than a decade, ending an 8-year period of negative rates. Going forward, the ECB will face a difficult balancing act. While persistently high inflation calls for further rate hikes, there are significant downside risks to economic growth, including disruptions to gas supply and growing divergence of member States’ borrowing costs.

The Fed’s policy shift, coupled with a strong dollar, has further increased the pressure on central banks in developing countries to tighten monetary policy. In many cases, most notably in Latin America, central banks had already started raising interest rates in 2021, taking an increasingly aggressive tightening stance in 2022. However, monetary tightening, so far, has had only a very limited impact on inflation. This is mainly because the current bout of inflation is not primarily caused by excess demand, but rather by a combination of persistent supply shortages, rising international commodity prices, and downward pressure on national currencies. Central banks in developing countries are thus also facing difficult policy choices. Aggressive monetary tightening may do little to bring inflation down but could cause an economic downturn and undermine recovery from the pandemic. Overly loose monetary policy, on the other hand, may prolong inflationary pressures and increase the risks of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations.

Rising borrowing costs and worsening liquidity conditions hit developing countries

Amid high inflation and aggressive policy rate hikes, financial conditions are tightening, borrowing costs are rising, and liquidity is shrinking. In developed countries, sovereign-bond yields have increased, while equity prices have declined amid spikes in volatility. Rising production costs and lower profit margins have also led to widening corporate bond spreads, with corporate bond yields surging to the highest levels since the global financial crisis. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the dollar has further appreciated against the euro, the yen, and the pound sterling as well as most developing country currencies.

Tighter monetary conditions and declining liquidity have raised the risks of disorderly adjustments in financial markets, with further declines in housing and asset prices in developed countries. With investors’ risk appetite falling, capital flows to emerging economies have declined markedly. Between February and July 2022, the 3-month moving average of capital flows fell from $11.2 to – $6.2 billion (figure 5). Bond issuance in the first quarter of 2022 was weaker than in any first quarter since 2016. Commodity-exporters from Latin America and Western Asia have seen more resilient flows, though.

Tightening fiscal space in developing countries: between a rock and a hard place

The current global environment, with slowing economic growth, rapidly tightening global financial conditions and a soaring dollar, threatens to exacerbate fiscal and debt vulnerabilities in developing countries. Sovereign bond spreads have increased across developing countries in 2022 (figure 6), particularly among commodity-importers. The unprecedented measures taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis have helped prevent economic collapse and limit social damage but have left Governments with record levels of debt burdens and major fiscal challenges. Servicing the debt is becoming increasingly expensive, taking up an ever-growing share of revenues and constraining fiscal space. Also, tightening financial and capital market conditions are worsening “rollover” risks for many developing countries, pushing them towards debt defaults.

A growing number of developing countries find themselves in precarious debt situations. According to the IMF, 39 out of 69 low-income countries are now at high risk of or already in debt distress. Moreover, middle-income countries with market access also face mounting financial pressures. A record 21 emerging market sovereigns’ dollar bonds are trading at distressed levels – with yields more than 1,000 basis points (10 percentage points) above US treasuries of the same maturity. Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Zambia are already in default, after the COVID-19 crisis exacerbated long-standing debt problems. Several other countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, are at the brink of default. Even if the scenario of widespread debt distress and disorderly defaults does not materialize, heightened fiscal consolidation pressures threaten to trigger large cuts to public investment and social spending. This, in turn, would undermine economic recovery and cause further setbacks to sustainable development.

Multiple crises demand strengthened and more effective global cooperation

The pandemic, the global food and energy crisis, the ever-worsening climate catastrophe, and the looming debt crisis in developing countries are testing the limits of existing multilateral frameworks. Many countries have responded to new challenges and threats by adopting more inward-looking policies. Such reactions are misguided and short-sighted, however, as many of the current crises are global in nature and strongly interlinked. With an estimated 657 million people living in extreme poverty and the number of acute food-insecure people rising sharply, scaling-up international cooperation and development finance is critical at this juncture.

Official development assistance (ODA) from the Development Assistance Committee members remained at about 0.33 per cent of their combined gross national income in 2021, far below the 0.7 per cent target established by the General Assembly in 1970. Current levels of ODA remain inadequate for meeting the targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including those related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. To address the looming debt crisis in developing countries, bold, comprehensive, and forward-looking measures are needed. Existing mechanisms for highly indebted developing countries must be significantly improved and expanded.

Under the G20 ‘Debt Service Suspension Initiative’ (DSSI), which was established in May 2020 and ended in December 2021, bilateral official creditors suspended debt service payments from the poorest countries. By temporarily providing liquidity relief, the DSSI allowed countries to concentrate their resources on fighting the pandemic and mitigating the economic and social fallout. Overall, 48 out of 73 eligible countries participated in the initiative, which delivered an estimated total debt service suspension of $12.9 billion. While the DSSI offered breathing space, it did not address solvency problems as the amount of debt owed was not reduced (in other words, the suspension was net present value neutral). In addition, private creditors did not participate in the DSSI and middle-income countries were not eligible.

In view of these limitations, the G20 launched the ‘Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI’ in November 2020. This initiative aims to help the 73 DSSI-eligible countries deal with insolvency and protracted liquidity problems. When public debt is deemed not sustainable, the initiative can provide a deep debt restructuring, reducing the net present value of debt to restore sustainability. When debt is deemed sustainable, but liquidity issues exist, a portion of debt service payments can be deferred for several years to ease financing pressures. So far, however, only three countries—Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia—have requested debt relief under this framework and, in each case, the process has been very slow. This reflects difficulties in reaching agreement among official creditors (which include Paris Club members as well as China, India, and other countries) and in getting private creditors on board. Unlike in the DSSI, where private creditor participation was voluntary, the Common Framework requires private creditors to participate on comparable terms to overcome collective action challenges and ensure fair burden sharing. Moreover, some countries are reluctant to agree to an IMF-supported programme—a precondition to participating in the common framework—due to potentially strict austerity measures.

Even if the current shortcomings and obstacles of the Common Framework can be addressed, it is unclear if widespread debt crisis and fiscal crunch can be avoided. In many cases, the net present value of debt will need to be reduced swiftly and sharply. Otherwise, sovereign default or painful adjustments via cuts in development spending will only be delayed.

The Economics Behind the President’s Economic Agenda

Over the past several decades, the United States has failed to make important investments in its economy and underlying infrastructure. This has resulted in unequal economic growth and an economy that is not delivering the living standards it could. A common issue with these problems is that the private market cannot be expected to solve them on its own. When the benefits to the country as a whole outweigh those to the individual or private firm, or when capital markets do not operate smoothly, there is a critical role for government.

As a result, strong, stable, and shared growth can be achieved when the public sector is viewed as a partner, not rival to private sector activity. President Biden has signed into law or proposed billions of dollars with this partnership in mind. Taken as a whole, three legislative measures—the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the proposed Inflation Reduction Act—will support productivity and help ensure that the U.S. economy not only continues to grow, but also works for the American people by promoting good jobs, increasing equity, and putting the United States at the forefront of the clean energy revolution. These bills will expand our economy’s productive capacity to drive sustainable economic growth, improving living standards and lowering prices over time

This blog focuses on how this trio of legislative measures address three long-standing problems that hinder economic growth: access to the internet, the fragilities of America’s supply chains, and the rise of increasingly costly climate disasters.

Supporting access to the internet

Economic growth is not only reliant on building people’s skills, but also on ensuring that people can fully utilize those skills in the economy, driving productivity and innovation. In the Economic Report of the President, CEA laid out how public investments in education and training are critical for economic growth, but investments that help people access the economy are also important. When public investments enable everyone to fully participate in the economy, employment outcomes and productivity improve, which supports economic growth. This set of economic capacity-building legislation expands the ability of people to participate in economic activity in a number of ways.

One example is broadband. Reliable broadband internet has become increasingly essential to economic activity and job creation because it enables more people to access economic opportunities—and likely has positive impacts on health and educational outcomes. In response, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s Affordable Connectivity Program focuses on ensuring widespread access to this critical infrastructure by reducing the cost of broadband internet and providing one-time discounts on laptops, desktops, and tablets. With these discounts, access to the internet should be free for the majority of eligible Americans. These investments are particularly important for reducing economic disparities, as survey data from January and February 2021 indicate that people of color, lower-income Americans, and Americans in rural communities are particularly likely to lack access to broadband internet. The BIL has already reduced the cost of broadband internet for roughly 13 million American households (and counting).

Strengthening supply chain efficiency and resilience

A strong economy can recover more quickly from unusual events—including evermore frequent billion-dollar natural disasters—and that requires supply chains that are both efficient and resilient. Such supply chains must therefore have the ability to secure key inputs both from across the United States and abroad, and have the infrastructure necessary to move these inputs efficiently and safely until they reach the end consumer. This is fundamental to the scaffolding that all economic actors rely on.

The past few years have revealed vulnerabilities in some of our supply chains, with adverse effects on American producers and consumers. The three pieces of legislation together address various aspects of these vulnerabilities that the private sector cannot adequately address on its own. For example, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes historic investments to improve the infrastructure that physically connects points of the supply chain, including ports ($17B), roads and bridges ($110B), and the rail system ($66B).

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored that some inputs are so critical to our economy that we cannot rely exclusively on foreign sourcing for their supply. In particular, semiconductors are now basic components in a vast array of products, from consumer electronics, to automobiles, healthcare equipment, and weapons systems. According to analysts, in 2021, global semiconductor shortages affected at least 169 different industries in the United States. Ready access to key technology components is now critical to national security. To address these deficiencies, CHIPS provides roughly $52B in grants, loan guarantees, and other support to improve the U.S. semiconductor supply chain, while the BIL provides more than $7B for the battery supply chain.

Smoothing the transition to clean energy and addressing climate change

A strong, stable economy requires a smooth transition to clean energy with a need for public investment along the innovation pipeline—from investments in research, development, and demonstration, all the way to commercialization. Without bold action, the damages from climate change will continue to be costly and fall disproportionately on lower-income communities, which are more likely to be directly impacted and least able to protect their residents. It is also clear that there is substantial opportunity to lead the world on the production of clean energy technologies. President Biden has set ambitious goals to lower U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, with a near-term goal of 50 percent of 2005 levels by 2030. Recent legislative accomplishments will push toward that, reducing U.S. emissions while lowering energy costs for households and creating high-quality jobs.

For example, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law invests in building a nationwide electric vehicle (EV) charging network. Widespread adoption of EVs is necessary for reducing transportation emissions, which made up 27 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. However, current charging infrastructure is inadequate to support largescale EV adoption. According to one projection, meeting the Administration’s goals for EV adoption by 2030 will require 1.2 million public chargers (Figure 1). While many chargers will come from private sources, particularly as EV adoption rises, a recent economic paper concludes that government investment in EV chargers is the most cost-effective way to support adoption of EVs.

The BIL also invests in clean energy demonstration projects that will be critical to successful innovation efforts to address climate change. Demonstration projects are needed to avoid the “valley of death” that emerging technologies can fall into between successful research and commercialization efforts, which happens when investors will not take on the large costs and risks associated with the first several commercial deployments of complex, largescale, low-carbon solutions.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) would build on these economic investments by supporting the transition to sustainable energy sources. Independent estimates have found that the IRA will be critical for reducing U.S. emissions, and this law on top of BIL and other existing measures would put the United States on track to reduce emissions by roughly 40 percent of 2005 levels by 2030.

These investments would lower energy costs for American consumers. For example, the International Energy Agency recently declared solar energy the cheapest electricity source in history. The hundreds of billions of dollars of proposed investments in clean energy in the IRA would accelerate the deployment of a variety of new clean energy solutions that would benefit American households and position American firms and workers to be leading suppliers of energy projects at home and abroad.

Conclusion

These examples are only emblematic of the historic investments within these three pieces of legislation, as they contain much more. The legislation also includes measures to lower prescription drug costs for many Americans, maintain important health insurance affordability, and increase resources for the Federal government—including shoring up the ability of the Internal Revenue Service to ensure our tax code is enforced fairly. Combined, these bills will drive American competitiveness, address climate change, support good jobs across the United States, and lower costs for families. Fundamentally, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the proposed Inflation Reduction Act are all grounded in the idea that the public sector must effectively partner with private actors. While there is still much more to be done, this trio of economic capacity-building legislation is a historic down payment towards achieving sustainable growth that is broadly shared.